|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

1750

GIANFRANCESCO COSTA (1711 -1772)

An

interesting engraving comes to us by way of Costa who shows a portable

tent camera standing on what appears to be four legs, in his book

‚€˜Delicie del Fiume Brenta‚€™. The portable camera is attended

to by two people who are rendering a drawing from across a canal,

of a church and row of houses.

Costa's

engraving from 1750 (left) depicting the open-air use of

a tent camera obscura. Two people appear to be manipulating the

camera in gathering a view of the community along a canal. This

'on location' illustration comes from Costa's book ‚€˜Delicie

del Fiume Brenta‚€™. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1752

JOHN HINTON ( - )

Although

not the inventor, Hinton published an illustration of a room camera

obscura in his publication, ‚€˜Universal MagazineOf Knowledge

And Pleasure‚€™.

Hinton's

illustration (right) from his 'Universal Magazine'.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

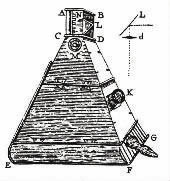

1752

ABB√‰ NOLLET (1700 - 1770)

Nollet

made a camera obscura (as did many others) not only portable, but

also collapsible. The portable camera obscura had to this point

become a necessity to travelers and those active out of doors. Just

like today, a camera was then becoming something that you would

not leave home without. This collapsible camera obscura of Nollet

is unquestionably similar to one made by a Mr. Thompson who is spoken

of by Joseph Harris in 1775. |

| Abbe

Nollet received a patent for this camera obscura (left) after submitting

the design to the French Royal Academy of Sciences in 1752. This

was a collapsible camera with a pyramid frame. The upper left diagram

shows it in it's collapsed state. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1753

SIMON PARRAT ( - )

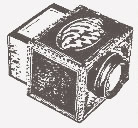

Parrat

described a 'Showbox' in a letter sent to the

‚€˜Gentleman's Magazine‚€™. As Parrat was describing the use

of this instrument in great strides, it is unclear whether he himself

built it, or was simply praising it. Easily converted into a camera,

it was typically used for viewing drawings or engravings. |

|

| A

showbox of questionable origin (right). We do know that Parrat,

an Englishman, knew of this instrument, but whether he built it

is another question, and not answered here. This showbox for viewing

engravings and the like, could be converted to become a camera obscura

as well. The lens was located at (CD) and an image was viewed at

the back (AB) by pulling the string (F) to open the door (E). In

all it would be about 32 inches long, and 12 inches square at the

back. Parrat told of it in a letter sent to the Gentlemen's

Magazine, 1753. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

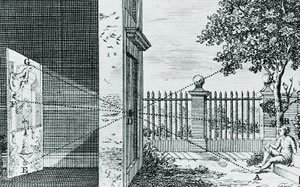

A room camera obscura

illustration from 1754 (left). This engraving appeared in

the New Complete Dictionary by Middleton and reminds

us of the showmen of the 14th and 15th centuries, as well as Edward

Scarlett's camera obscura projection into his shop. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1755

ABB√‰ NOLLET (1700 - 1770)

Another

portable camera obscura comes to us again by Nollet. This one is

illustrated as a tent camera that even though portable, can be used

well even at home.

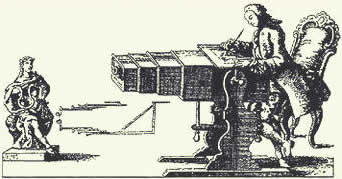

Nollet's

tent camera obscura (right) of 1755. The statuette under

the balcony acts as subject to the artist in the tent (balcony).

The telescopic lens-arm hanging over the balcony reflects the image

through the tube and into the tent from the top. The four-legged

tent on the ground (bottom right corner) shows us how the contrivance

appears in it's uncovered state. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

1756

LEONARD EULER (1707 - 1783) |

|

|

| |

The first reference found

of the use of the Megascope for projection is by the

German physicist Euler. In projecting opaque objects for Phantasmagoria

shows, the Megascope lens was used in conjunction with the Fantascope.

Today this application is known as an Episcope. The inspiration

for this technique came from Charles. SEE MOISSE

FANTASCOPE |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1758

JOHN DOLLOND (1706 - 1761) |

|

|

| |

Dollond, an optician,

improved upon the camera obscura especially in the area of lens construction

by manufacturing an achromatic lens which corrected fringes in colour

and allowing a much clearer picture. He achieved this through the use

of a crown glass lens and a flint glass lens. This method was found to

ignore chromatic aberrations. Dollond manufactured camera obscuras. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1760

CHARLES-FRANCOIS TIPHAIGNE DE LA ROCHE (1722 - 1774) |

|

|

| |

| De la Roche

wrote a book called 'Giphantie' in which he expounded

on a series of imaginary scenes. One, that of the main character

being taken in a typhoon, arrives in a land where he is shown wondrous

things were pictures are ‚€œmade‚€Ě.

A portion of the tale has his host telling how this is done, and

is as follows; |

| |

|

‚€œYou

know, that rays of light reflected from different bodies form

pictures, paint the image reflected on all polished surfaces,

for example, on the retina of the eye, on water, and on glass.

The spirits have sought to fix these fleeting images; they have

made a subtle matter by means of which a picture is formed in

the twinkling of an eye. They coat a piece of canvas with this

matter, and place it in front of the object to be taken. The first

effect of this cloth is similar to that of a mirror, but by means

of its viscous nature the prepared canvas, as is not the case

with the mirror, retains a fac-simile of the image.

The

mirror represents images faithfully, but retains none; our canvas

reflects them no less faithfully, but retains them all. This impression

of the image is instantaneous. The canvas is then removed and

deposited in a dark place. An hour later the impression is dry,

and you have a picture the more precious in that no art can imitate

its truthfulness.‚€Ě |

|

| |

| One

wonders which of the many examples of the past, (Statius, Villeneuve,

Cardano, Porta, et al) De la Roche may have drawn from, telling

this story. One element however is still unexplained. That is, what

‚€œthis matter‚€Ě is referring

to, in the coating of the canvas. La Roche was a doctor who wrote

many philosophical romances in the 18th century using alchemy and

magic as themes within science. Illuminism and Rationalism pre-date

his work and clearly influenced it. Like Verne, Orwell and others,

he foresaw the coming of inventions such as photography and motion

pictures. |

The

title 'Giphantie' was in fact an anagram of De La Roche's middle

name 'Tiphaigne'. |

Cover of Giphantie

(above)

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

1760

MARTIN FROBEN LEDERMULLER (1719 - 1769)

A

microscopist in his spare time, Ledermuller wrote ‚€˜Microscopic

Delights Of The Mind And Eye‚€™, 1760. He described and illustrated

several camera obscuras, some of which were designed as solar microscopes

to view insects. Both reflex and non-reflex cameras are illustrated.

Ledermuller's interest in insects-as-subjects came from his status

as government beekeeper.

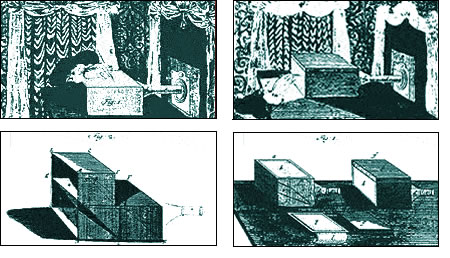

Ledermuller's

'Microscopic Delights Of The Mind And Eye' provided us

with several illustrations, four of which are included here (right).

The top images show the camera obscura up against a wall, which

could have contained the insects on the other side in some sort

of storage area. |

|

| It

may have been up against a blackened window. The solar microscope

is shown attached. The illustration on the top left depicts a reflex

camera with 45 degree mirror. The top right shows the camera without

the mirror. In the bottom right image we see the apparatus in sections

with the solar microscope attached. The right-most image shows (F)

as a roll of paper inserted between a sheet of glass and frame for

drawing purposes. Ledermuller provided these illustrations in colour. |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

ca. 1760

ABBE NOLLET (1700 - 1770) |

|

|

| |

Nollet constructed a children's

toy, which he named a ‚€˜Dazzling, Whirling, Top‚€™. The

amusement itself although not a magic lantern-type instrument, reminds

us of the yet-to-come zoetrope, and revolving wheels. This top of Nollet‚€™s,

when revolving at a fast speed re-created a sense of motion and had the

appearance of being a solid object. Nollet not only encouraged the camera

and lantern in entertainment but also in the use of education. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

1764

BENJAMIN MARTIN (1704 - 1782)

Camera

obscuras came in many forms such as the goblet camera of Herigone.

Martin provided us with a book-shaped camera measuring 24 x 18 x

5 inches in its folded state which he gave to Harvard following

a devastating fire which destroyed the school‚€™s contents. Martin

included with his gifts to Harvard, a camera obscura in the shape

of a brass eye.

The

book-shaped camera obscura shown here (left) is typical of

book camera obscuras of the mid 18th century. The famed portrait

painter Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792) owned this one. It is shown

open for use. (It sits at The

National Museum of Science & Industry). An

engraving of Benjamin Martin (right) from the Encyclopedia

of London 1815. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

1764

CHARLES A. PHILIPPE VAN LOO (1705 - 1795)

An

adorable painting of a camera obscura poking it‚€™s way into the frame

comes to us by way of Van Loo. The subjects are actually the artist‚€™s

family, who are overshadowed by the instrument. A fascinating study

of perspective and dimension, the painting named, "The Magic

Lantern‚€Ě is rather mis-named. It shows a young boy in the

background looking into the lens while embracing the camera, and

a little girl in the foreground with her hand on the frame with

fingers outside of what would be the natural boundaries of a posed

environment. The camera although half in the picture, is clearly

not a magic lantern, but appears from the left as if ‚€œentering‚€Ě

into the view. This added ‚€˜3rd‚€Ě dimension reminds us of the natural

environment the camera obscura provided to artists. The wooden box

and lens are not peculiar to a lantern, and there appears to be

no chimney. However, the circular frame is typical of the shape

of lanternslides. It is unclear why Van Loo called the painting

as he did. This historian has suggested that the view we see is

in fact that of a lanternslide as it would appear in painted form,

thus the name, and the slight humour in blending the two discoveries

in the same picture. It is not known if Van Loo painted lantern

slides. The painting resides in the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

|

|

| Van

Loo's mis-named painting (right) of 1764, "The Magic

Lantern". Clearly the instrument is a camera (having no

characteristics to that of a lantern), even to the novice student.

The portrait of Van Loo's family represents the finished work of

the camera obscura, as opposed to the lantern. It's obvious Van

Loo never used the camera in his art. |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1769

GEORG FRIEDRICH BRANDER (1713 - 1785)

Brander

was German, and published a book, ‚€˜Beschreibung dreyer Camerae

Obscurae‚€™ (Augsburg, 1769) in which he illustrated

a ‚€˜desk‚€™ camera obscura capable of allowing the ease of large drawings.

The apparatus which one could actually sit at was at least 4 feet

high with an extended aperture, which appears to be of equal length.

The artist would sit like as to write a letter and see the subject

before him through the aid of a 45¬į mirror within the camera. Brander

was a student in mathematics and physics at Nuremburg and later

wrote several books on the camera obscura. He edited ‚€˜Beschreibung

dreyer Camerae Obscurae‚€™ twice, in 1775 and 1792. |

|

| Georg

Friedrich Brander provided us with this (right) large and

very practical desk camera obscura illustration from his ‚€˜Beschreibung

dreyer Camerae Obscurae‚€™ of 1769. One could just imagine

the view through the desktop as the artist rendered his subject.

It stood approximately four feet high with a similar length. The

extentions seen housing the aperture allowed for close-ups or telephoto

images. Likely, in this drawing the artist had a close-up of the

subject with a head and shoulders picture, the lens being extended

as it is. |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

ca. MID

18TH CENTURY

GEORGES DESMAREES (1697 - 1776)

Another camera obscura

finds its way into a painting (bottom right corner) by Desmarees,

of German artist Joachimus Franciscus Beich. The portrait of Beich

shows another ‚€˜painting within a painting‚€™ with a cherubim with

a magnifying glass looking at the subject who appears within an

almost circular frame (magnified image typical of a zoom lens).

The camera obscura is found outside this frame, in the bottom right

of the picture as a reminder of it‚€™s abilities to enlarge. A mezzotint

engraving of this exact painting is found at George Eastman House

in Rochester New York. It is said by Coke (One Hundred Years

Of Photographic History, Essays In Honour Of Beaumont Newhall, Edited

by Van Deren Coke, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque,

p130) that the camera obscura in this painting is of the same

make used by Caneletto, (original constructed by Venetian optical

instrument maker, Selva). The one in the painting is a German model.

|

| Desmarees'

painting (above) of Beich provides us with a splendid view

of a small camera obscura outside the portrait itself. The juxtaposed

portrait would indicate a subjective view of what the camera sees.

And the magnifying glass in the child's hand? Perhaps it suggests

the ability of the camera to enlarge the image. |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

18TH CENTURY |

|

|

| |

During the 18th Century

and the first half of the 19th, the camera obscura was embraced more by

artists than by scientists. It was encouraged to be used for drawing,

sketching and painting. Masters such as Caneletto and Vermeer were often

linked to the camera obscura and controversies have arisen due to this

point. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

ca.

1770

MEGASCOPE

The

Megascope was a camera obscura which was able -

through the use of a larger lens - to make large scale images of

smaller objects. The Megascope became fairly popular

in the 18th and 19th centuries. Additional mirrors were used to

supremely illuminate the subjects. A focal length of plus 30 inches

were typical. In 1872 Guillemin will publish his ‚€˜The Forces

Of Nature‚€™, outlining the megascope along with illustrations

(The Forces of Nature, A. Guillemin, 1872, London).

|

|

| One

of Guillemin's illustrations from his book 'The Forces of

Nature', published in 1872. The megascope shown here (above)

reminds us of a typical room camera obscura except that the focal

length (sometimes longer than 30") was great enough to fill the

room inside. Notice an exterior mirror at a 45 degree angle downward

to illuminate the subject (a simple lighting effect still used today

by television and film crews). In or around 1770 the megascope began

to appear in books and journals. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1770

ABB√‰ GUYOT ( - )

Publishes

his ‚€˜Nouvelles Recr√©ations Physiques et Math√©matiques‚€™

(Paris, 1770) with an illustration (vol. 3, plate

20) of an upside down pyramid camera obscura with legs, or,

a table camera obscura. The instrument was said to be 2 feet high

and had it‚€™s lens about 2-3 inches off the ground. It could have

been used for outdoor scenes, placed close to a window. If the

curtains were drawn, this would allow enough darkness for a more

brilliant screen. It might also allow for secrecy in that the

subject may not know they were being sketched. Hooper, in 1787

will describe this apparatus in 'Rational Recreations‚€™.

Guyot's

table camera obscura (right) of 1770. The surface viewing

area received the projected image from below with the lens about

2 inches off the ground. Perhaps the camera was a simple novelty

for guests or a conversation piece. Of course, it could also be

used for drawing. The illustration appeared in Guyot's

‚€˜Nouvelles Recr√©ations Physiques et Math√©matiques‚€™.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

ca. 1770

THOMAS SHERATON (1751 - 1806)

This

furniture maker in London produced what could be the smallest camera

obscura yet known of. Measuring just 2 x 3 x 3 inches, this supposed

gift was a box within a box. The smaller, inner box slid out of

the larger one, allowing a focus. The lens was in the larger, outer

box and fixed.

The

English furniture maker Thomas Sheraton made a somewhat intricate

pocket camera (left) in or around 1770. Along with the camera

in the handle of a cane, and Herigone's goblet, this camera obscura

is one of the smallest to date. |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1770

JOHANN GEORG SCHROPFER (1730 - 1774) |

|

|

| |

This German, in Lepzig,

began using phantasms and the like in some presentations which preyed

upon the superstitious. Eighteen years later Robertson would gain notoriety

for the very same magic lantern shows using smoke, mirrors, mobile lanterns

and multiple lanterns. Schropfer was a necromancer who eventually committed

suicide. He practiced witchcraft and persauded many to follow him into

the occult. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1772

JOSEPH PRIESTLEY (1733 - 1804)

Finished and published

his ‚€˜History and Present State of Discoveries Relating

to Vision, Light and Colours‚€™. He states that Kircher

did ‚€œmore conveniently‚€Ě

in the night, what Porta did in the day. He gave inventors credit

to Porta, describing his ‚€œtheatrics‚€Ě

in introducing the camera obscura into history. Priestley is

noted as the discoverer of; graphite (carbon) being a conductor

of electricity; carbon dioxide; soda; nitrus oxide; oxygen;

photosynthesis; and the eraser made from India gum (coining

the phrase 'rubber'). |

|

|

|

| |

|

Joseph

Priestley |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

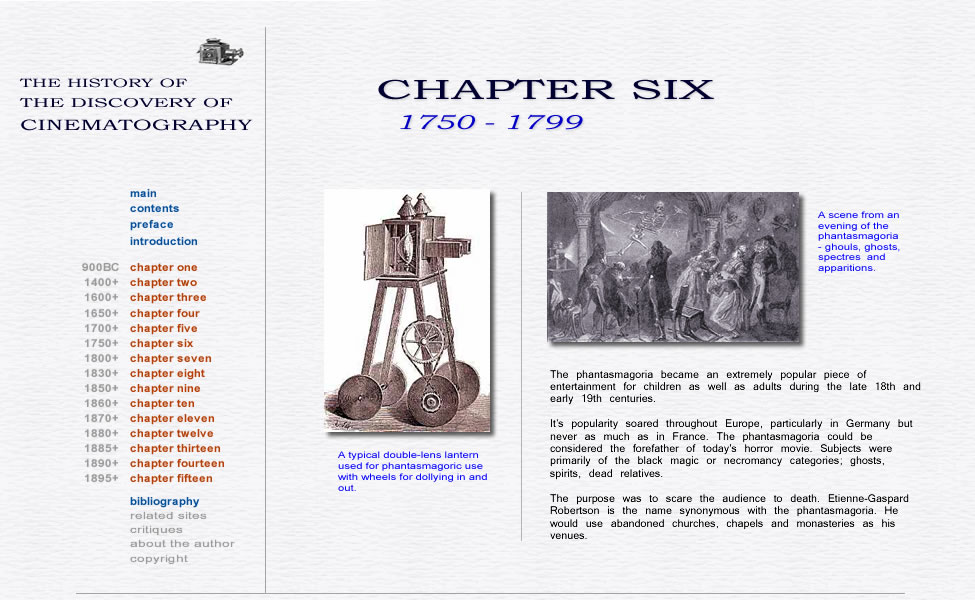

PHANTASMAGORIA

The Phantasmagoria

became an extremely popular piece of entertainment for

children as well as adults. It‚€™s popularity soared throughout Europe,

particularly in Germany but never as much as in France. Born of

a combination of the Shadowplay, the magic lantern

and the desire to deceive or trick, the Phantasmagoria

could be considered the forefather of today‚€™s horror movie. Its

basic purpose was to produce through simple techniques, an illusion.

Subjects were primarily of the black magic or necromancy categories;

ghosts, spirits, dead relatives or personalities and politicians.

The purpose was to scare the audience to death. Techniques included

the use of smoke, the Shadowplay, use of two or

more magic lanterns, rear projection, hidden projection, projection

on glass, use of mirrors, projection from below the stage, movement

of the lantern (hidden) offering the illusion of subject-motion

and many other ingenious moves.

(Image Courtesy Toronto Reference Library)

ITINERANT TRAVELLING

SHOWMEN

Magic

lanterns also played a part in certain conjuring shows put on by

travelers well versed in such trickery. There are reports dating

back to antiquity which suggest that such tricks were known using

other mediums. Such showmen were common in the streets of European

cities during the 18th and 19th centuries. The great magician Robertson

had at the time of the French Revolution, an elaborate system which

made the effigies of the dead appear to his stunned audiences. He

compensated the movement of the lantern (s) by changing the position

of the lens and thereby was able to show a figure growing larger

and remaining in sharp focus throughout the show. In this manner

he obtained the compelling impression of an approaching figure.

|

| Dissolving

Views within the magic lantern would become an important

fare of the traveling man in the next century. Traveling from city

to town, the traveling magic lantern showman was a virtual cinema

on legs. He carried his lantern, oil, slides and stories with him

on his back. Sometimes traveling in pairs in order to share the

audio/visual element of the program and to attract more patrons,

their shows were known as Galantee So. This the English

title given, comes from the meaning of a 'fine show'. Only

the 'show' part was mispronounced through the accent of the showman

to come out as 'so'. Catching on more and more as the century

wound down, slide shows of the traveler were mostly as those of

the static lantern found in homes of the time; Biblical themes such

as Judgment Day, Noah, Christ on the cross and a vivid hell for

the cheater. |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1772

FRANCOIS DOMINIQUE SERAPHIN (1747 - 1800) |

|

|

| |

One man, Francois Seraphin,

was one of the first to bring the Shadowplay into France.

He called it the ‚€˜Ombres Chinoises‚€™. Seraphin performed

before royalty which was at that time, a very popular and inviting venue.

His first performances of deception were at the Palace of Versailles.

His shows lasted through the French Revolution and into the next century.

Marionettes, a French entertainment-art, had dominated

France until this time as the number one form of movement re-creation

in artistry, and never would regain its hold on audiences as it had. The

magic lantern and the phantasmagoria would for the next one hundred years

hold that title, until the coming of cinema in 1895, at another French

venue, the Grand Cafe in Paris. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

1773

JOSIAH WEDGEWOOD (WEDGWOOD) (1730 - 1795)

Father of Thomas, this

famous maker of pottery introduces the camera obscura into the

Wedgewood home.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1773

J. H. LAMBERT (1728 - 1777) |

|

|

| |

Lambert wrote ‚€˜Nouveaux

Memoires de l‚€™ Academie Royale‚€™ in which he documents the use

of the camera obscura to record cloud height. A German physicist, Lambert

found a scientific use for the camera which was rare, or at least, poorly

documented. Previously, cloud height had been detected through observance

of the shadows on the ground. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1775

JOSEPH HARRIS (1702 - 1764) |

|

|

| |

Harris wrote ‚€˜Treatise

of Optics‚€™ but it was not until this year that it was published,

after his death (London, 1775, 2nd Book, pp 269-282). It describes

using many fine depictions, the image made with a lens. Besides telling

how one could make a camera, and the uses of the ox-eye lens, Harris also

suggests the ‚€œpocket camera‚€Ě with

a lens of 1 1/2 inch focus which could be fitted to the handle of a cane. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1777

MATTHEW BOULTON (1728 - 1809)

There are many commentaries

of which suggest that Boulton may have produced photographs

at his establishment, Boulton & Watt, this year. Jerome Harrison

for one, states in his ‚€˜A History Of Photography‚€™,

(Scovill, New York, 1887) these were of the aquatint

process, mechanically produced on metal, large scale, 4 feet

by 5 feet, and coloured (p13, ch. 2). Harrison further

states that this process was that of an employee of the factory,

one Mr. Francis Eggington, inventor. Boulton‚€™s grandson will

discredit these claims however, in a pamphlet published in 1865.

It should be noted that Francis Eggington in his own right became

well known for his work in enamelled glass and stained glass,

as well as his work alongside Boulton in reproducing oil paintings

using a mechanical process. |

|

|

|

| |

|

Matthew

Boulton |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

1777

CHARLES (CARL) WILLIAM SCHEELE (1742 - 1786)

Scheele was considered

a great chemist, and had been working with silver chloride and

sunlight. He found and proved that the different hues of the

spectrum had substantially different effects on silver when

exposed. He noted that the darker colours such as purple and

blue turned silver chloride darker and faster, than red or yellow.

Scheele also confirmed the fact that light is what affects the

nitrate base, and not heat, as has been suggested and believed

to this point by some. Even beyond this point in time, there

were some who continued to document heat to be the agent in

action, regarding silver salts and the like SEE

1798 RUMFORD |

|

|

|

| |

Scheele's Home Pharmacy

& Laboratory |

Charles

W. Scheele |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

1778

WILLIAM STORER ( - )

William

Storer was an English instrument maker. He produced a camera obscura

of such technical superiority that it was named the Royal

Accurate Delineator. Utilizing rack and pinion motion,

Storer‚€™s camera contained two boxes, one sliding within the other

and had two lenses in the aperture. A third lens allowed for a

brilliant picture and clear focus, however the depth of field

was lessened. A Storer Delineator resides at the Science Museum,

London.

A

William Storer camera obscura 'delineator' (left) of

1778. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

1780

JACQUES ALEXANDRE CESAR CHARLES (1746 - 1823)

Charles was commissioned

by Louis XVI to construct (at the Louvre in Paris) a projection

machine known as a Magascope which would project

images of people onto a wall.

Charles is also known

in history as the man who invented the hydrogen balloon. |

|

|

|

| |

|

Jacques A. C. Charles |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1781

PHILIPPE JACQUES DE LOUTHERBOURG (1740 - 1812) |

|

|

| |

In 1781 Loutherbourg,

an accomplished painter, put the finishing touches on what he called an

Eidophusikon which attempted to present motion through

the presentation of successive pictures. Based loosely on the camera obscura

room and it's ability to entertain crowds, and leaning more towards the

Panorama and Diorama, the Eidophusikon was first

set up in a room in his house. Guests would peer through an aperture no

less than 6 feet square to see pictures painted on fine tafata with colours

which were translucent. Light was projected from behind at different distances

depending on the desired effect. Reflecting mirrors were added to define

the scenery with brilliance and life.

In his Musical Memoirs of 1830, Parke would comment on

the Eidophusikon as the ...."newly

invented transparent shades upon which was shed a vast body and brilliancy

of colour producing an almost enchanting effect." A darkened

auditorium aided Loutherbourg in setting a mood consistent with the program,

and agreeable to the audience. It would be another hundred years however,

before patrons would sit in theatres with only the screen/stage lit. Loutherbourg's

first showing was that of an early morning scene of London. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

AUTHOR'S

NOTE:

Loutherbourg has also been associated with the names Lauterbourg

and Lutherbourg. Adolf Hübl in a 1947 published work was

announced by the German film director Werner Wekes as a post-biblio 'source'

for his 1986 documentary on the prehistory of cinema, and links Loutherbourg

as the inventor of the Flip Book in 1760. No other reference

has been found. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1784

FRANCOIS DOMINIQUE SERAPHIN (1747 - 1800) |

|

|

| |

Begins performing his

Shadowplays at the Palais Royale in Paris. The magic

lantern had grown in such popularity as a form of contemporary entertainment,

that the Royal court was now the ultimate venue. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1784

ETIENNE - GASPARD ROBERT (1764 - 1837) |

|

|

| |

Robert, from Belgium,

changed his name early on to the lengthier Robertson. He maintained this

stage name for the most part, throughout his entire life and was well

known as E.G. Robertson the master of the Fantasmagoria.

Robertson probably did more for the art than any other magician, performer

or showman. His Fantasmagoria grew out of an early interest

in and love for magic, or more importantly, optics. A professor of physics

in his native Liege, he states in his memoirs that he read the works of

Porta and Kircher et al, and began on the road to horror by devising what

would become the most prolific entertainment of the late 18th and early

19th centuries. In 1784, Robertson gave an exhibition of an improved magic

lantern. He was greatly influenced by the earlier work of Musschenbroek‚€™s

motion attempts, and had been impressed with the works of the Shadowplay

artists including Seraphin, a decade earlier in Paris. Robertson headed

towards Paris with his ‚€˜Fantomes Artificiels‚€™ (Artificial

Fantoms). |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

ca. 1785

GIUSEPPE BALSAMO (1743 - 1795) |

|

|

| |

Also known as ALESSANDRO

CONTE DI CAGLIOSTRO or COUNT CAGLIOSTRO, this Italian itinerant traveling

showman and perhaps charlatan, was known for using Fantasmagoric

imagery and Shadowplays of a deceptive nature in order

to deceive patrons and was jailed several times. Balsamo became quite

popular throughout Europe, and well known we might add. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

1786

GILLES LOUIS CHRETIEN (1754 - 1811)

Produced

his process of making multiple ‚€œsilhouettes‚€Ě which he called a ‚€˜Physionotrace‚€™.

As was the silhouette, an outline of the subject was made along

with a matching copper engraving. The copper plate was then used

for reproductions. (SEE 1687 MARCO ANTONIO

CELLIO for similarities in copperplate etchings).

This

portrait of Chretien was made in 1792. The Physionotrace

was invented by Chretien in 1786 and produced a product similar

to the silhouette in appearance. It also allowed the user to trace

smaller etchings and engravings. |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1787

ROBERT BARKER (1739 - 1806) |

|

|

| |

Barker receives this

year a patent for a new form of entertainment which contained huge painted

pictures. It is recorded on the patent as "an entire new contrivance

or apparatus called by him 'La nature a coup d' oeil' ."

Barker, having spent some time in jail, was said to have needed light

in order to read a letter and came up with the idea of lighting from

above when using a shaft of light falling through a crack. Barker, a

Scottish painter, had seen the work of Loutherbourg and his backlit

spectacles. Barker's entertainment became known as the Panorama.

The Classic Encyclopedia based on the 11th edition

of the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica defines the Panorama

and explains it as ... "the name given

originally to a pictorial representation of the whole view visible from

one point by an observer who in turning round looks successively to

all points of the horizon. In an ordinary picture only a small part

of the objects visible from one point is included, far less being generally

given than the eye of the observer can take in whilst stationary. The

drawing is in this case made by projecting the objects to be represented

from the point occupied by the eye on a plane. If a greater part of

a landscape has to be represented, it becomes more convenient for the

artist to suppose himself surrounded by a cylindrical surface in whose

centre he stands, and to project the landscape from this position on

the cylinder. In a panorama such a cylinder, originally of about 60

ft:, but now extending to upwards of 1 3 0 ft. diameter, is covered

with an accurate representation in colours of a landscape, so that an

observer standing in the centre of the cylinder sees the picture like

an actual landscape in nature completely surround him in all directions.

This gives an effect of great reality to the picture, which is skilfully

aided in various ways. The observer stands on a platform representing,

say, the flat roof of a house, and the space between this platform and

the picture is covered with real objects which gradually blend into

the picture itself. The picture is lighted from above, but a roof is

spread over the central platform so that no light but that reflected

from the picture reaches the eye. To make this light appear the more

brilliant, the passages and staircase which lead the spectator to the

platform are kept nearly dark." |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

PANORAMA and DIORAMA |

|

|

| |

These enormously popular

forms of entertainment were the closest things to an actual movie theatre

in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. They required great artists

who excelled in perspective and large-scale productions. Besides Loutherbourg,

Thomas Gainsborough and Louis Daguerre also provided spectacular scenery.

Daguerre would open the first Diorama in Paris in 1822.

So popular were they that several other 'versions' came out of them. Some

were known as; Pleorama, Giorama, Cyclorama, Betaniorama, Cosmorama,

Kalorama, Kineorama, Europerama, Typorama, Neorama, Uranorama, Octorama,

Poecilorama, Physiorama, Nausorama, Udorama.

The Panorama was unique in the sense that one could not

only see the centre of the picture but also, the peripheral vision could

see as in nature, the outer corners of the view. This gives us the sense

that there is no boundary other than the limitations of the eye itself.

Today's Panorama is of course, the Cinerama,

more commonly known as the IMAX format (IMAX incorporating

height as well as width). The Panorama was also

the precursor of the 1930's and 40's newsreels of the movie theatre. Patrons

could not only see the film but prior to it's beginning, news footage

of recent events, news happenings and the like would be shown fresh from

the battlefield or street scene. In 1812, a Panorama

in Berlin was presenting the burning of Moscow just three months after

it happened. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1790

PIERRE GUINARD ( - ) |

|

|

| |

Guinard greatly advanced

the process of grinding glass into finer lenses for optical use. Guinard

was a Swiss glassmaker. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1792

ROBERT BARKER (1739 - 1806) |

|

|

| |

Barker makes his first

public presentation of his new Panorama at Leicester

Square, London in 1792. Patrons sat in the centre of a slowly revolving

rotunda, which measured 16 feet high and 45 feet in diameter. The view

was of the British navy moored between the Isle of Wight and Portsmouth

and was named The English Fleet. Shortly thereafter,

Barker toured with his Panorama showing such epics as

View of London, Battle of Aboukir, The Environs of Windsor and Lord

Howe's Naval Victory. While touring in Germany, his show was given

the unfortunate German translation of Nausorama. The Panorama

was as wide as 300 feet and as high as 50. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

1792 Panoramic Painting

From The Top Of St. Giles Church |

|

| |

One of Robert

Barker's 'new contrivance or apparatus called by him 'La nature a

coup d' oeil'. This panorama (above) by Barker is of the

city of Edinburgh. These enormous paintings were a pre-cursor to today's

wide-screen cinema. Edinbugh Castle can be seen to the right. Barker ironically

was also a painter of miniatures. The above Panorama of Robert Barker

is from The Edinburgh Virtual Environment Centre at The University of

Edinburgh and is © the City Arts Centre. it is entitled "Edinburgh

From The Crown Of St. Giles". Thanks to John Hadden.

|

|

| |

View

A Large Format Of This Digitized Panorama Here. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

2004 Panoramic

Photograph From The Scott Monument |

|

| |

A superb

modern-day panoramic photograph of Edinburgh from a different vantage

point (immediately above). As Barker's panorama of the late 1790's

was painted from the crown of St. Giles, this 2004 photograph by photographer

John Loughlin was taken from the Scott Monument. Locating the castle on

the horizon off the right border, one can follow the city landscape as

well as landmarks and roads down the Royal Mile. Photograph Source: John

Loughlin |

|

| |

View

A Large Format Of This Digital Photograph Here. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

2004 Panoramic

Photograph From The Edinburgh Camera Obscura |

|

| |

This marvelous

panoramic photograph taken by photographer Peter Stubbs is from the Edinburgh

camera obscura. It was taken in 2004 and is more than 360 degrees as Edinburgh

Castle can be seen on both the far left and far right edges. Stubbs used

twelve photogaphs to complete this image. The camera obscura building

can be seen on the far right, above the two lasses. Visit Edin

Photo here for an annotated view. Photograph Courtesy Peter Stubbs

© (www.edinphoto.org.uk) |

|

| |

View

A Large Format Of This Photograph Here |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1794

ELIZABETH FULHAME ( - ) |

|

|

| |

A Scot, Fulhame was the

wife of a doctor who had an interest in producing images. Possibly influenced

by her husband, she wrote and published 'An Essay on Combustion:

With a View to a New Art of Dying and Painting' this year. Fulhame

wrote on the need for a 'catalysis' in decelerating the action of light

on silver and gold compounds and conducted experiments on reducing oxidation.

Through her husband Thomas she came into contact with men like Joseph

Priestley. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

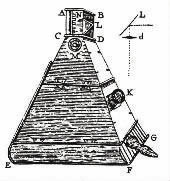

1794

THE ENCYCLOPEDIA BRITANNICA of 1794 ... |

|

|

| |

. . . provides us with

another book-form camera obscura. This illustration depicts a camera which

when unfolded, appears in the shape of a pyramid. It allows the hand of

the illustrator to be inserted in order to make the drawing. It also had

a knob which could be turned and thus control the lens, allowing a clear

focus. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

AUTHOR‚€™S NOTE:

Numerous entries such as this

are found throughout time and therefore are consuming to say the least.

We therefore reserve the right to document those entries we feel are significant

to the theme of this book, and discard others we feel are repetitive or

duplicative, and do not contribute to the meaning of discovery, although

historical. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

Another book camera

obscura with a pyramid-shape when unfolded. This illustration (left)

appeared in the 1794 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. In

comparison to Guyot's table camera (SEE ABB√‰ GUYOT)

of 1770, this model is a righted version. The mirror (L) and lens

(d) were stored in the top (ABCD). The base (GFE) took the shape

of the "book" when collapsed and not in use. A knob was located

at (M) [below the top] which could be turned to focus. The viewer

looked through (K) to see the image. A cloth-covered entrance between

(FG) allowed the user to insert the hand if the picture was to be

drawn. |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1796

JEAN-GABRIEL AUGUSTIN CHEVALLIER (1778 - 1848)

|

|

|

| |

Chevallier was optician

to the King as well as an engineer. He was also a manufacturer of scientific

instrument s including optical pieces beginning this year. Chevallier

sold Phantasmagoria magic lanterns including a machine

which could mimic the sounds of thunderstorms. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1796

ETIENNE-GASPARD ROBERT (1763 - 1837) |

|

|

| |

Proposes to the French

government his ‚€˜Miroir d'Archimede‚€™ or Mirrors of

Archimedes and a plan for burning the invading ships of the English

navy. The plan was refused and from this point he concentrated on the

magic lantern and a more entertaining host. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1796

THOMAS WEDGEWOOD (WEDGWOOD) (1771 - 1805) |

|

|

| |

Wedgewood experimented

with silver salts making images of leaves and insects using silver nitrate

on a number of different bases including leather. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

1797

ETIENNE-GASPARD ROBERT (1763 - 1837)

Robertson

is given permission to present a magic lantern show within a chapel

on the property of a Capuchin monastery. The chapel was abandoned

and presented as the ideal venue for his phantoms, spectres and

gouls. Robertson used his mobile lanterns (several), smoke, mirrors

and the lively imaginations of the patrons of Paris. He also used

rear projection and projection on gauze that was coated with wax

which he ironed to produce a translucent appearance. |

| Robertson

used a variety of techniques and strategies in order to scare his

audiences to death. His famous show at the monastery near the Palace

Vendome created a stir not lived down too soon. Using huge sheets

of glass, roving lanterns, smoke and mirrors, Robertson became the

talk of Europe and the phantasmagoria soon made its way to North

America. |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

1797

GIOVANNI BATTISTA VENTURI (1746 – 1822)

Venturi decodes the

mirror writing of Da Vinci and publishes his work showing detailed

and scientific descriptions of the camera obscura and the pinhole

image as seen by Da Vinci (Essai sur les ouvrages phisico-mathematiques

de Leonardo da Vinci, Paris, 1797). Venturi became

professor of geometry and philosophy at the University of Modena

in 1773 and physics in 1776 also at Pavia.

In 1814 Venturi wrote his

'Commentari sopra la storia e le teorie dell'ottica'

(Bologna, 1814) on the history of optics. SEE

DA VINCI 1500 |

|

|

|

| |

|

Giovanni

Battista Venturi |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

1798

ETIENNE-GASPARD ROBERT (1763 - 1837)

Robertson

presented his first French exhibition of the Fantasmagorie

at the Pavillon de l'Echiquier in Paris. He used

a magic lantern that was on wheels for great effect in motion and

realism. In 1799 he obtained a patent naming the instrument a ‚€˜Fantoscope‚€™.

Robertson

was clearly the early master of the magic lantern phantasmagoria.

His concept of motion-projectors precedes the concept of dollying

and panning, which was born of the cinematographer in the early

20th century.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

1798

COUNT RUMFORD (BENJAMIN THOMPSON) also REICHSGRAF VON RUMFORD

(1753 - 1814)

Presented to the Royal

Society a paper entitled ‚€˜An Enquiry Concerning The

Chemical Properties That Have Been Attributed To Light‚€™.

Rumford claimed that heat caused silver salts to darken under

light and not the light. The Royal Society published this in

their Philosophical Transactions Journal. His

claims were directed towards Charles Scheele who had conclusively

shown the opposite.

During the American

Revolution Rumford took the side of the British. He moved to

Europe living in Germany and England, working with the poor

and continuing his experim ents and studies in heat.

Rumford is known today

for the 'Rumford Fireplace' and also as the inventor of thermal

underwear. The Rumford crater on the moon is named after him.

SEE 1777 SCHEELE |

|

| |

Count

Rumford |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

1799

ETIENNE-GASPARD ROBERT (1763 - 1837) |

|

|

| |

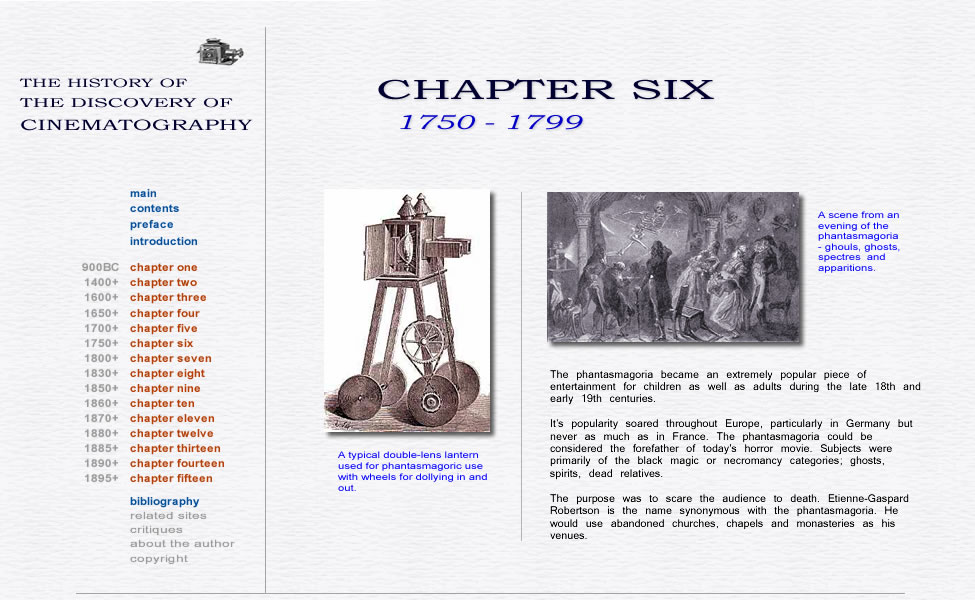

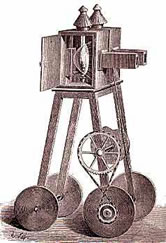

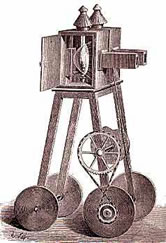

Robertson applied for

and obtains a patent for his portable ‚€˜Fantoscope‚€™, a

magic lantern on wheels. . . . A representation

of a magic lantern on wheels used for recreating motion during phantasmagoria

shows of the late 18th and early 19th century. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |